On Saturday, in a extract from the late Jan Morris’s mesmerising memoirs, one of Britain’s best-loved travel writers revealed her remarkable transition from man to woman.

Here, she describes an altogether different journey — one that would be remembered as one of the greatest adventures on Earth…

My professional life began with an imperial exploit. On May 29, 1953, Mount Everest, Chomolungma, the supreme mountain of the world, was climbed for the first time by Sir John Hunt’s British expedition.

It included two New Zealanders, a famous Sherpa mountaineer from the Everest foothill country and a team of Sherpa high-altitude porters.

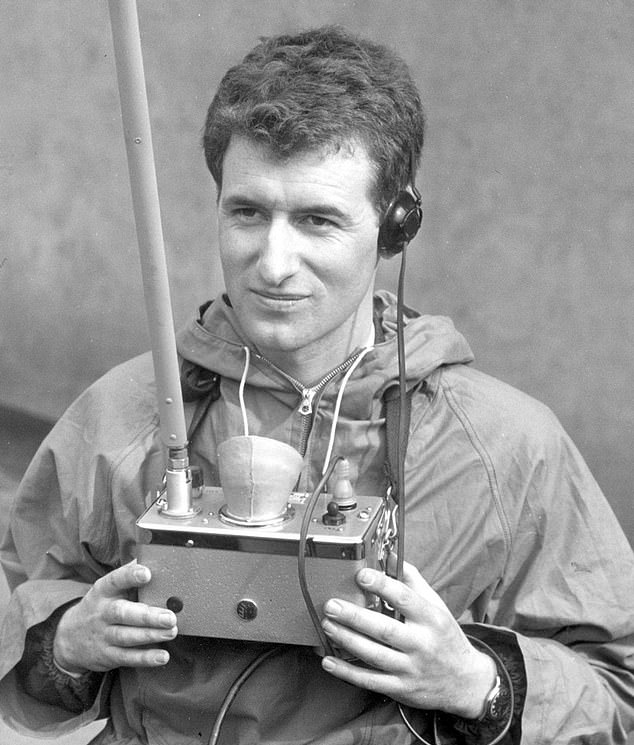

I went with them on behalf of The Times, as the only reporter with the expedition, and the experience provided me with my one big scoop (pictured: Morris in radio contact)

I went with them on behalf of The Times, as the only reporter with the expedition, and the experience provided me with my one big scoop (as we called it in those days).

The ascent was the last such achievement of the British Empire, and it was capped by the circumstance that my report of it was published in London on June 2, 1953, the very morning of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II — the start, as it was fondly thought then, of a new Elizabethan age.

On the afternoon of May 30, I was with Hunt and most of the climbers some 22,000ft up, awaiting the return of the New Zealander Edmund Hillary and the Sherpa Tenzing Norgay from their attempt upon the summit. We didn’t yet know whether they had got there.

‘There they are!’

I rushed to the door of the tent, and there emerging from a little gully, not more than 500 yards away, were four worn figures in windproof clothing.

As a man we leapt out of the camp and up the slope, our boots sinking and skidding in the soft snow.

I was awaiting the return of the New Zealander Edmund Hillary and the Sherpa Tenzing Norgay from their attempt upon the summit (pictured)

Wildly we ran and slithered up the snow, and the Sherpas, emerging excitedly from their tents, ran after us.

Down they tramped, mechanically, and up we raced, trembling with expectation.

Soon I caught sight of George Lowe, leading the party down the hill. He was raising his arm and waving as he walked! It was thumbs up!

Everest was climbed! Hillary brandished his ice axe in weary triumph; Tenzing slipped suddenly sideways, recovered and shot us a brilliant white smile; and they were among us, back from the summit, with men pumping their hands and embracing them, laughing, smiling, crying, taking photographs, laughing again, crying again, till the noise of delight rang down and set the Sherpas, following us up the hill, laughing in anticipation.

As Tenzing approached them they stepped forward, one by one, to congratulate him. He received them like a modest prince.

Some bent their heads forward, as if in prayer. Some shook hands lightly and delicately, the fingers scarcely touching.

One veteran, his black twisted pig-tail flowing behind him, bowed gravely to touch Tenzing’s hand with his forehead.

We moved into the big dome tent and sat around the summit party throwing questions at them, still laughing, still unable to believe the truth.

Everest was climbed, and those two men in front of us, sitting on old boxes, had stood upon its summit, the highest place on Earth! And nobody knew but us!

The day was still dazzlingly bright — the snow so white, the sky so blue; and the air was still so vibrant with excitement; and the news, however much we expected it, was still somehow such a wonderful surprise — shock waves of that moment must still linger there, so potent were they, and so gloriously charged with pleasure.

Jan Morris (pictured) describes an altogether different journey — one that would be remembered as one of the greatest adventures on Earth…

International competition for the news was intense, so I scuttled down the mountain that same evening, and by skulldug means sent my first report of the ascent off to London.

When two days later I followed it away from Everest with my Sherpa helpers, I did not know whether I had assured my scoop, or whether the news had been intercepted and the story filched by some competitor even more unscrupulous than I was myself.

It was June 1. The evening air was cool and scented. Pine trees were all about us again, and lush foliage, and the roar of the swollen Dudh Khosi rang in our ears.

On the west bank of the river there was a Sherpa hamlet called Benkar. There, as the dusk settled around us, we halted for the night.

In the small square clearing among the houses Sonam set up my tent, and I erected the aerial of my radio receiver.

The Sherpas, in their usual way, marched boldly into the houses around about and established themselves among the straw, fires and potatoes of the upstairs rooms.

Soon there was a smell of roasting and the fragrance of tea.

As I sat outside my tent meditating, with only a few urchins standing impassively in front of me, Sonam emerged with a huge plate of scrawny chicken, a mug of chang (alcoholic porridge), tea, chocolate and chupattis.

How far had my news gone? I wondered as I ate. Was it already winging its way to England from Kathmandu, or was it still plodding over the Himalayan foothills? Would tomorrow, June 2, be both Coronation and Everest Day?

Or would the ascent fall upon London later, like a last splendid chime of the abbey bells?

There was no way of knowing; I was alone in a void; the chicken was tough, the urchins unnerving. I went to bed.

But the morning broke fair. Lazily, as the sunshine crept up my sleeping bag, I reached a hand out of my mummied wrappings towards the knob of the wireless.

A moment of fumbling; a few crackles and hisses; and then the voice of an Englishman. Everest had been climbed, he said.

Queen Elizabeth had been given the news on the eve of her coronation. The crowds waiting in the wet London streets had cheered and danced to hear of it.

After 30 years of endeavour, spanning a generation, the top of the Earth had been reached and one of the greatest of adventures accomplished.

This news of Coronation Everest (said that good man in London) had been first announced in a copyright dispatch in The Times.

I jumped out of my bed, spilling the bedclothes about me, tearing open the tent flap, leaping into the open in my filthy shirt, my broken boots, my torn trousers.

My face was thickly bearded, my skin cracked with sun and cold, my voice hoarse. But I shouted to the Sherpas, whose bleary eyes were appearing from the neighbouring windows:

‘Chomolungma finished! Everest done with! All OK!’

‘Ok, sahib,’ the Sherpas shouted back. ‘Breakfast now?’

It has often been suggested that The Times delayed publication of the news of the ascent in order to make it coincide with the Coronation. What a canard! We had no long-distance radios on Everest, and I nearly killed myself slithering down the mountain to get the news home in time.

To safeguard my scoop I put my message in code. I had devised it simply for a final announcement of success, this is how it read: SNOW CONDITIONS BAD (= summit reached) ADVANCED BASE ABANDONED (= Hillary) AWAITING IMPROVEMENT (= Tenzing) ALL WELL (= nobody hurt).

My dispatch reached the paper safely, although it didn’t make the front page because it was another 13 years before news stories were printed on the front page of The Times.

Stories were published anonymously in those days, so I got no byline, and it was three years before I was able to publish a book about the adventure: Coronation Everest.

When we returned to London from Nepal we were invited to a celebratory dinner at Lancaster House, the government’s official place of entertainment.

I found myself sitting next to the major-domo of the occasion, a delightful elderly courtier of old-school charm, while opposite me sat Tenzing Norgay, away from Asia for the first time in his life.

The old gentleman turned to me halfway through the meal and told me the claret was the very last of its particularly good vintage from the cellars of Lancaster House, and possibly the last anywhere in the world. He hoped I was enjoying it.

I was much impressed, and looked across the table to Tenzing, who most certainly was.

He had probably never tasted wine before, and he was radiant with the pride and pleasure of the occasion — a supremely stylish and exotic figure.

The lackeys respectfully filled and re-filled his glass.

Presently, my neighbour turned to me once more. ‘Oh, Mr Morris,’ he said in his silvery Edwardian cadence, ‘how very good it is to see Mr Tenzing knows a decent claret when he has one.’

- Conundrum, by Jan Morris, is published by Faber at £10.99. © Jan Morris 1974. To order a copy for £9.67 go to mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3308 9193. Free UK delivery on orders over £15. Promotional price valid until December 12.