Why bookshops are literally to die for: Martin Latham, who has sold books for more than 30 years, explores the history of books, and why we love them so much

- Martin Latham, manager of Waterstones in Canterbury, tells the bookseller’s tale

- He explores the history of book and packs the memoir with touching stories

- ‘Unstuffy’ about books he shares why he once chucked one out of a window

MEMOIR

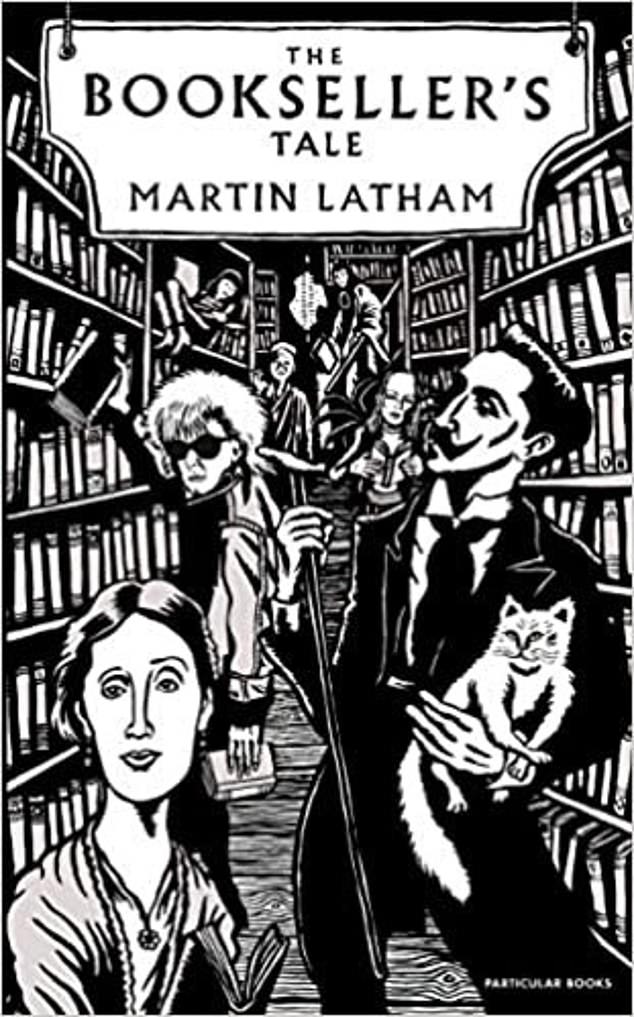

The Bookseller’s Tale

by Martin Latham (Particular Books £16.99, 368 pp)

Sir Anthony Hopkins was once offered a part in the film version of George Feifer’s novel The Girl From Petrovka. He couldn’t find a copy of it anywhere. Then, while waiting for a Tube train, he looked down to find a copy on the bench next to him.

Two years later, having made the film, he told Feifer what had happened. The author replied that he had lost his own copy, complete with notes, after lending it to a friend. Hopkins checked — the book he’d found was the very same one.

Even when they’re not leading to such staggering coincidences, books are wonderful and powerful things. Martin Latham, who has sold them for more than 30 years (he’s now manager of Waterstones in Canterbury), has done the tradition proud. His exploration of the history of books, and why we love them so much, is packed with touching stories and fascinating facts. We learn that Alexander the Great carried Homer’s Iliad with him everywhere. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes, read the novels of Sir Walter Scott by candlelight in ‘the dead of night . . . the sense of crime added zest to the story’.

The Bookseller’s Tale by Martin Latham (Particular Books £16.99, 368 pp)

Some people take their relationships with books to an even higher level. ‘Women will with surprising frequency kiss a book after buying it,’ says Latham. ‘This does not, the women I have asked tell me, happen with the superficially more sensual purchase of clothing.’ But the prize for most extreme reaction goes to 17th-century Christian converts in Virginia, who were so excited about receiving Bibles carried by ships from England that they stripped off and rubbed the holy texts all over their bodies.

Latham is refreshingly unstuffy about books. ‘A toddler and I were once so annoyed by a fairy tale I was reading out,’ he recalls, ‘that we agreed to throw it out of the open second-floor bedroom window. Doing so was cathartic.’

You sense his disapproval of writer A. S. Byatt, who bought one of Terry Pratchett’s Discworld novels from his shop in Kent, saying she loved the fantasy series ‘but I can’t be seen buying it in London’.

Some of the best stories in the book are about marginalia, the thoughts and comments jotted down by readers at page edges. Chairman Mao and Adolf Hitler both littered their books with ‘self-justifications and apocalyptic predictions’, while Marlene Dietrich’s German dictionary had just one word underlined: ‘Kraut’. It was Ernest Hemingway’s nickname for her. She had a lifelong unconsummated passion for him.

The book is packed with a host of interesting facts on authors and books you will never have heard before

Sometimes marginalia are more entertaining than the text itself. ‘I’m going to punch this book in the face if it makes this point again,’ wrote one scribbler. An Oxford student adorned a dull textbook with: ‘Christ, I’ve left the oven on.’

Bookshops themselves are as varied as their stock. Serendipity Books in Berkeley, California, stocked more than a million books — all arranged entirely at random. ‘If you’re focused,’ said the bad-tempered owner, ‘go to a library.’

In World War II the WHSmith on the Rue de Rivoli in Paris was staffed by the occupying Gestapo (‘Imagine the customer service’).

While working in a shop in London, Latham served the actor Sir Michael Hordern who’d come in for a book on how to cook, as his wife of 40 years had just died. He chose Delia Smith’s One Is Fun. At the till he sighed: ‘One is not, though.’

Underpinning the whole narrative is that simple pleasure, the love of a good book. Latham writes about the noble tradition of slowing down at the end to delay having to finish (by the end of Keith Richards’s autobiography I was rationing myself to individual paragraphs).

And he tells the story of the woman who had a heart attack in his shop. As she was wheeled out to the ambulance she held Latham’s hand. ‘I do love it here,’ she said. ‘It would have been a great place to go.’